© Katy Derbyshire

Going Dutch with German Writers (17): Boys at the Bechereck

A night of pool, mystery schnapps and bluffing about poetry in Neukölln turns out not as daunting as Katy Derbyshire feared. With so many friends in common, how can she and Jan Skudlarek run out of conversation material?

Who?

Jan Skudlarek is a poet from somewhere in Westphalia. He’s 28 and published his debut collection, Elektrosmog, in 2013. He’s lived in Berlin-Neukölln for three years.

Where?

Bechereck, Neukölln

What?

We order beer when we arrive, and Jan asks if we should have a Mexikaner to go with it. I’m surprised because for me, a Mexikaner is something to round off the end of an evening. But Jan says it’s a classic Herrengedeck. For those who don’t speak German: a Mexikaner is a shot of schnapps (I think tequila, Jan thinks gin and vodka) with tomato juice and Tabasco. And a Herrengedeck – literally a gentleman’s place setting – is when you have a beer and a schnapps in front of you at the same time. We start with the Mexikaner and it’s excellent; really thick and soupy. I don’t ever want to spoil the magic by finding out what’s in it.

What did we talk about?

A mutual friend recommended I should go out drinking with Jan because he’s good fun. And I thought it would be a good idea because I’ve never been out drinking with a poet before. He doesn’t know much at all about me, and I don’t know much at all about him, and I think we start out with the usual “how long have you lived in Berlin” pleasantries and a bit of “my, how Neukölln’s changed”. Jan tells me he studied in Münster before he moved here, and we chat about Münster for a while and then of course about Tatort, because the only things I know about Münster is that it has a university and is a setting for Germany’s favourite crime show. We’re both rather take-it-or-leave-it about Tatort, neither lovers nor haters.

© Katy Derbyshire

We have a hell of a lot of mutual acquaintances, as we establish over the course of the evening. Jan translated a poem by an American woman I know, Lyz Pfister, and he tells me he underestimated how much hard work it would be. He says he saw her reading at an event that wasn’t part of the usual Young German Poets circle; there were bands playing and poets he’d never heard of. I’m pleased there’s someone out there who manages to cross the great German-English divide in the Berlin literary scene. As I see it, there are two parallel universes of German poets/prose writers and Anglophone poets/prose writers, and I keep wishing they’d come together and assuming the answer must be translation, but not many people seem to be interested in seeing that happen. I have a little complaining session about organizing events that not many people attend. Oh, but there are so many events in Berlin, Jan consoles me.

I ask what ontology means.

© Katy Derbyshire

So whose work does Jan Skudlarek read? He mentions the Berlin poet Uljana Wolf being his first discovery when it came to contemporary writers. Mostly, he seems to read poetry. But we also get talking about the prose author Selim Özdogan from Cologne because he started out very close to hip hop, which Jan didn’t realize. He’s a major fan of Özdogan’s most recent novel, DZ, which is a kind of parable about how drug users go off into their own exploitative world. I liked it a lot too. No, it’s not as simple as a parable, says Jan, there are all sorts of great references in it too, and he tells me he keeps lending people the book. I recommend Zwischen zwei Träumen and offer to lend him my copy, but he says he feels bad about not spending money on other people’s books.

Now he’s writing his PhD and it’s about, let me get this right, the ontology of intentions. I ask what ontology means. It’s philosophy, in his case philosophy of mind, and he’s interested in collective intentions. He gives me an example, presumably reduced to the bare bones: when Bayern Munich want to win some cup or other (no, neither of us are football fans), does that mean every single player in the team wants to win the cup individually or is there a collective intention to win the cup? Is there a “we” for intentions? That’s how I understood it, anyway. That’s really interesting, I say, and Jan says yes, it’s his party piece, and he looks a bit pained and I wonder just how much he’s simplified the concept for my sake. So what about when people identify with teams, I ask, like when the world cup is on and people say, “We’re in the semi-final!” when of course they’re not personally playing? I find those nationalisms troubling because the “we” seems so exclusive to me, and I’ve come across it in subcultures as well. He doesn’t feel comfortable with the whole “Wir sind Deutschland” sloganeering, says Jan, and I certainly don’t because I don’t feel included in that “we”. But I think that’s not actually what he’s working on.

So is the poetry scene a collective entity? Early in the evening, Jan says oh yes, definitely, and he talks about the “scene” in a way that makes it seem inclusive, warm and supportive. Poets buying and reading each other’s books, attending events, exchanging ideas. He’s part of a literary magazine, S T I L L, and he seems to relish the opportunity to publish other people’s work. Later, once I’ve corrupted him with my bitching about a certain mutual acquaintance, he does admit that there are some young poets he considers overhyped. In between, to my relief, he tells me I’m not the only one who can’t take in poetry when it’s read aloud at events. Phew.

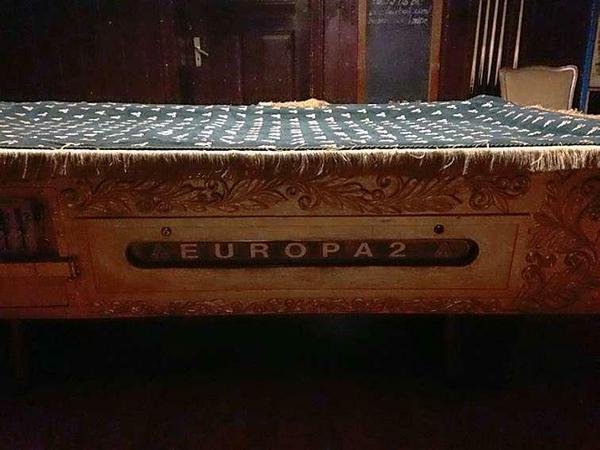

The Bechereck is a strange place. It’s dimly lit and most of it is laid out like a typical Neukölln corner bar, with one room dominated by a pool table and one by a dark counter. I don’t play pool or darts, so we sit in what they call the “living room”, where they’ve stripped the walls and put in sofas and a football table. I like it; the woman behind the bar is friendly and comes through to offer us a round of Mexikaner because she’s bored – it’s really quiet for a Friday night because everyone’s still exhausted from the Mayday holiday, she says. But I can’t get my head around the crowd – I was expecting hard-drinking old men but there are young English-speakers instead. My, how Neukölln’s changed. After a while we go and explore the room with the pool table, where the walls are decorated with collages I assume come mostly from the second-hand shops on nearby Flughafenstraße. The barwoman is playing Ike and Tina Turner and telling off a dog with a very waggy tail.

© Katy Derbyshire

It’s not often I go out drinking with a man so much younger than me as Jan. I was worried about it beforehand, and maybe we look a bit of an odd couple. But in fact it’s no big deal. In fact, Jan is astounded by how young other people are – he says they get submissions to S T I L L from people born in 1999, and it won’t be long now until they cross the millennium threshold. He came to poetry late, he says, at twenty (I try not to smirk), but there are kids out there at the Treffen Junger Autoren, for instance, and they’re fifteen and they know all the contemporary poets and all the publishers. He was still reading Gottfried Benn at that age!

He's very much of a boy.

© Katy Derbyshire

For much of the time when we talk about poetry, I am bluffing. I know the names of German poets and sometimes their faces, but I can rarely match them up to their actual work. Jan doesn’t seem to mind. He competed in the very prestigious Open Mike competition for writers under 35, twice – was that more like Miss World, with back-stabbing and bitching, or more like a class trip? Oh, much more the class trip, is his initial reaction. But in fact he means afterwards, when all the contestants went on a workshop weekend, whereas at the competition itself they were all nervous and didn’t know each other, and then he didn’t win and someone wrote something rude about him on the internet.

Google results. That particular posting has gone way down to page seventeen when you google Jan Skudlarek, he says. He’s perfectly open about wanting to get more good stuff onto the internet so that it covers up the bad stuff, the embarrassing things from his youth. Is it the same with his poetry – does he see his earlier work as “sins of his youth”? To some extent, yes, he doesn’t write now like he did in 2008, when he first started publishing work. He doesn’t want people to have that stuff at the forefront of their minds when they think of him. Is it like with huge rock stars who get pissed off with playing their hits? Not so much, he says, but he is now facing that “difficult second album” phase. He doesn’t want to be a one-hit wonder. But what if writers took all the time in the world for that one hit and made it as good as they possibly could, and then they wouldn’t have to keep churning out books? Ah, but that’s not the way the business works. Poets especially make money out of readings, not books, and you don’t get invited to read if your last book’s five years old. What I like a lot about poets is that they have day jobs. Jan’s thinking about what to do for money once he’s finished his PhD, but he wants to find a job he enjoys rather than something soul-destroying that he hates but does it anyway because his art is the sole focus of his life. I like that.

For a poet and philosopher, Jan Skudlarek is incredibly down to earth. He’s very much a boy – he likes hip hop and horror films, and I tell him he doesn’t match up very well to the cliché of the effete male poet. I’m a bit embarrassed that I said that. Two other boys are playing pool; one of them is very bad at it indeed, and hasn’t yet developed the tact not to position his backside in my face when lining up a shot. He’s wearing his trousers pulled down over his underpants, as the kids do, and his underpants are purple gingham boxers. I know this because after a while I stop looking away politely. They obviously feel at home here – there’s a laptop on the counter and they choose their own music on it, like a new-fangled jukebox. Something from the Balkans, I think – Jan likes it; I was happy with Ike and Tina. It’s an odd place but nice and friendly.

While they’re playing, Jan and I talk about yet another mutual acquaintance who’s just come back from New York, with a literary grant of some kind. We both really like him, but he kept posting photos on Facebook that made us green with envy. The guy knows perfectly well that everyone hates looking at his photos, but he’s cool enough to do it anyway. What do people do in New York, I ask, and why do we all want to go there? Neither of us know but we still want to go one day. I work out that the coolest people I know are either in New York or Berlin. Maybe we just want to go there so we can hang out with cool people. This is a reassuring thought because we can do that here too. I think maybe there are people in New York right now talking about how much they want to come to Berlin. They’re probably imagining sitting in a dimly lit pool room with beer and Mexikaner, bitching about poets.

Hangover?

Delayed-onset dull throbbing around the eyes, accompanied by general grumpiness.

- showPaywall:

- false

- isSubscriber:

- false

- isPaid:

- showPaywallPiano:

- false